Venues

Missouri Theatre

The Missouri Theatre Theatre Center for the Arts (203 S. Ninth St., 875-0600) is Columbia's last and grandest movie palace. It opened in 1928 with Buster Keaton's Steamboat Bill Jr. In 1953, Commonwealth Theatres bought the theater and ran it into the ground in the 1980s before selling it to United Artists, which wanted to gut the theater to make it into a multiplex. Thankfully, it was saved in 1987 when the Missouri Symphony Society bought it for their new home. In 2001, Ragtag and the symphony society began raising funds for a new projector; on November 15, 2002, the theater showed its first 35 mm feature in almost 15 years, a sold-out screening of Sing-along Sound of Music. Since then, Ragtag and MOSS have presented film events including the mid-Missouri premieres of Bowling for Columbine, Winged Migration and An Inconvenient Truth. After a multi-million-dollar makeover, the Missouri Theatre opened again May 21, 2008, and has quickly taken its place as mid-Missouri's premier showplace.

Blue Note

The Blue Note (17 N. Ninth St., 874-1944, www.thebluenote.com) has been a Columbia institution for concerts, dances and other shows since 1980. The seed was planted in 1975 when Philadelphia native Richard King, on his way to California, made a detour to visit a friend going to graduate school at MU. Five years later, King partnered with Phil Costello, a bartender at a place on the Business Loop called Brief Encounters (now Club Vogue). They bought the bar and renamed it the Blue Note, and it soon became a haven for the best independent rock of its day, including Hüsker Dü's last show, the Pixies and the Replacements. Then in the late '80s, while drinking at Booches, King learned that an old vaudeville house, the Varsity Theater, was for sale. By March 1990, after major improvements, King moved the Blue Note there. King continues to renovate the theater — including the restoration of tiered theater seating in the balcony — as part of the downtown historic district. The Varsity Theatre (Blue Note) was built in 1927 by Tom C. Hall, a prominent businessman who was also involved with several other theaters in town, including the Hall Theatre, which he built on South Ninth in 1916.

Windsor Cinema

1405 E. Broadway — north side of Broadway, west of Ripley. Accommodating approximately 300 persons, this venue's name recognizes the gift of alumna Gertrude Windsor at the time the college built Wood Quadrangle in the early 1960s.

The Hive

1405 E. Broadway — north side of Broadway, west of Ripley. In non-fest times, the name Charters Auditorium recognizes the key role of Dr. W.W. Charters in shaping the curriculum of Stephens during most of the years when it was a junior college — the 1920s through the 1950s.

The Chapel

1306 E. Walnut — Stephens College. The Firestone-Baars Chapel, dedicated in 1957 as the Saarinen Chapel (a name it should still have), was one of the last works of Finnish architect Eero Saarinen, who died in 1961. His noteworthy career that included the Gateway Arch in St. Louis, the TWA Flight Center at JFK International Airport and the main terminal of Dulles International Airport near Washington, D.C. By the late 1930s, many people at Stephens College saw the need for a chapel solely devoted to student religious activities. In 1939, a group of seniors began a building fund which grew slowly; delays in construction resulted from two wars and the death of the designated architect, Eliel Saarinen, Eero's father. Because of its ecumenical concept, there are no permanent religious symbols or artworks either outside or inside the chapel. Religious groups of diverse faiths have used their own ritual symbols for more than a half century. This absence of permanent symbols results in a very plain exterior — a 21-foot square with an entrance on each of the four sides, corresponding to the cardinal points of the compass. When the college faculty included a professional organist, recitals occurred here, and many voice students performed their senior recitals. Students gathered for worship services and evening vespers, especially in the 1950s and 1960s. The chapel was the site of memorial services that included those following the assassinations of JFK and MLK. A college administration in the late 1970s removed the massive 4,000 pound cube of Indiana limestone which served as the original altar — cutting it apart to remove it from the building — making it ineligible as a historic landmark. President Dianne Lynch has launched another attempt to place the chapel on the National Register and revived Vespers services there, which compel today's students to put away electronic devices and remember what's important in life.

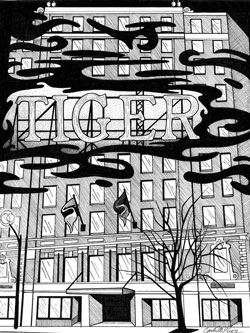

Forrest Theater @ Tiger Hotel

23 S. Eighth St., in Tiger Ballroom. Built in 1928 and, at nine stories, still the tallest building downtown, the Tiger Hotel and its impressive ballroom hosted Columbia's biggest social functions. It provided a convenient stopover for salesmen and other travelers who arrived by train. The rise of the automobile, however, sent the hotel into a long period of decline as new hotels popped up along the interstate. Originally, the Missouri Theatre planned to house a hotel above it, but when the owners of the Tiger heard about that, they threatened to put a theater in their building; cooler heads prevailed and they each carved out their own niche in the downtown. Ambitious plans to renovate the property over the years bankrupted several owners, but a massive renovation in the mid-1990s revitalized the hotel into a senior living center. In 2003, flush from the sale of some local radio stations, new owners bought it and are now converting it into a long-term residential hotel. They have restored the Tiger sign on the roof, a longtime downtown landmark, and erected new neon signs on the street entrance. For the festival, True/False renames the ballroom after local icon Forrest Rose, a well-loved columnist and stand-up bass player who passed away in March 2005 and whose graceful prose and soulful community spirit embody the very best of Columbia.

Ragtag Cinema (Big and Little)

10 Hitt Street, 441-8504, ragtagfilm.com. The Ragtag story begins in November 1997 when Paul Sturtz met David Wilson at a show by Mr. Quintron at the original Shattered ("in the broken heart of downtown") — now the space that is Cherry Street Artisan. The last downtown movie house had been shuttered by the corporate powers-that-be, and so they concocted the Ragtag Film Society. Richard King of the Blue Note gave them the OK to use that theater Sunday and Wednesday nights, and they launched the harebrained scheme in January 1998 with a couple of "borrowed" 16 mm projectors. The film society built a strong cult following over the next two years, and three bright entrepreneurs — medievalist Tim Spence, farmer Holly Roberson and baker Ron Rottinghaus — dreamed up the idea of making Ragtag a seven-day-a-week storefront cinema. And so, in May 2000, the Ragtag Cinema was born. Ragtag is often credited with saving Columbia, but people tend to exaggerate about such things. In February, 2008, Ragtag made the move to a warehouse from 1935, first used as a Coca-Cola Bottling factory and then as the Kelly Press printing plant, and lived happily ever after.

The Odd Fellows Temple

920 E. Walnut. This little-known and rarely-seen downtown landmark is owned by the local chapter of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows, whose mission is to "to improve and elevate the character of mankind." It is one of 10,000 lodges in 25 countries. The second floor hosted a sewing project designed to employ women during the Great Depression. The building appears to have housed government offices on most of the ground floor from the 1940s through 1968 or later, with the lodge hall above, and hosted the Ragtag Cinema between 2000 and 2008. It is one of the few, if not the only, historic lodge halls in downtown Columbia. The Odd Fellows' peak membership was on the eve of World War I, when the IOOF had 3.4 million active members, but the Great Depression caused a decline as fees became out of reach for some; additionally, the New Deal overlapped the social mission the group spearheaded. The IOOF claims be the largest fraternal order in the world under one head, and has generously lent the temple on the second floor to us for T/F weekend.

The Box Office (in the Hall Theater building)

100 South Ninth. Built as part of the movie palace, the Hall Theater, it is in a 1916 limestone-fronted building which predates the Missouri Theatre by more than a decade. During this time period, the shabby nickelodeon made way for the opulent movie palace as theater owners tapped into a new buying group — the middle class. While Spanish/Moorish was the most popular style of the 1920s, classical was the second most used. The classical revival 1,291-seat Hall Theatre had a stage built to show vaudeville and films, and measured 22'6" wide and 30' deep, the largest in the state outside Kansas City and St. Louis. It incorporated an advanced heating and cooling system.